Why Older Gardens Need a Different Pruning Philosophy Than Young Ones

Most pruning advice is written with young gardens in mind.

It assumes plants are vigorous, forgiving, and keen to respond. Cut back at the right time, make clean cuts, and the plant will reward you with fresh growth and renewed structure.

That logic holds — for a while.

Where it quietly breaks down is in older gardens, where the plants are established, growth has slowed, and tolerance for interference is far lower. In those settings, doing the right thing at the right time can still lead to disappointing results.

That realisation didn’t come to me from books or courses. It came from watching certain shrubs respond — or fail to respond — over many years.

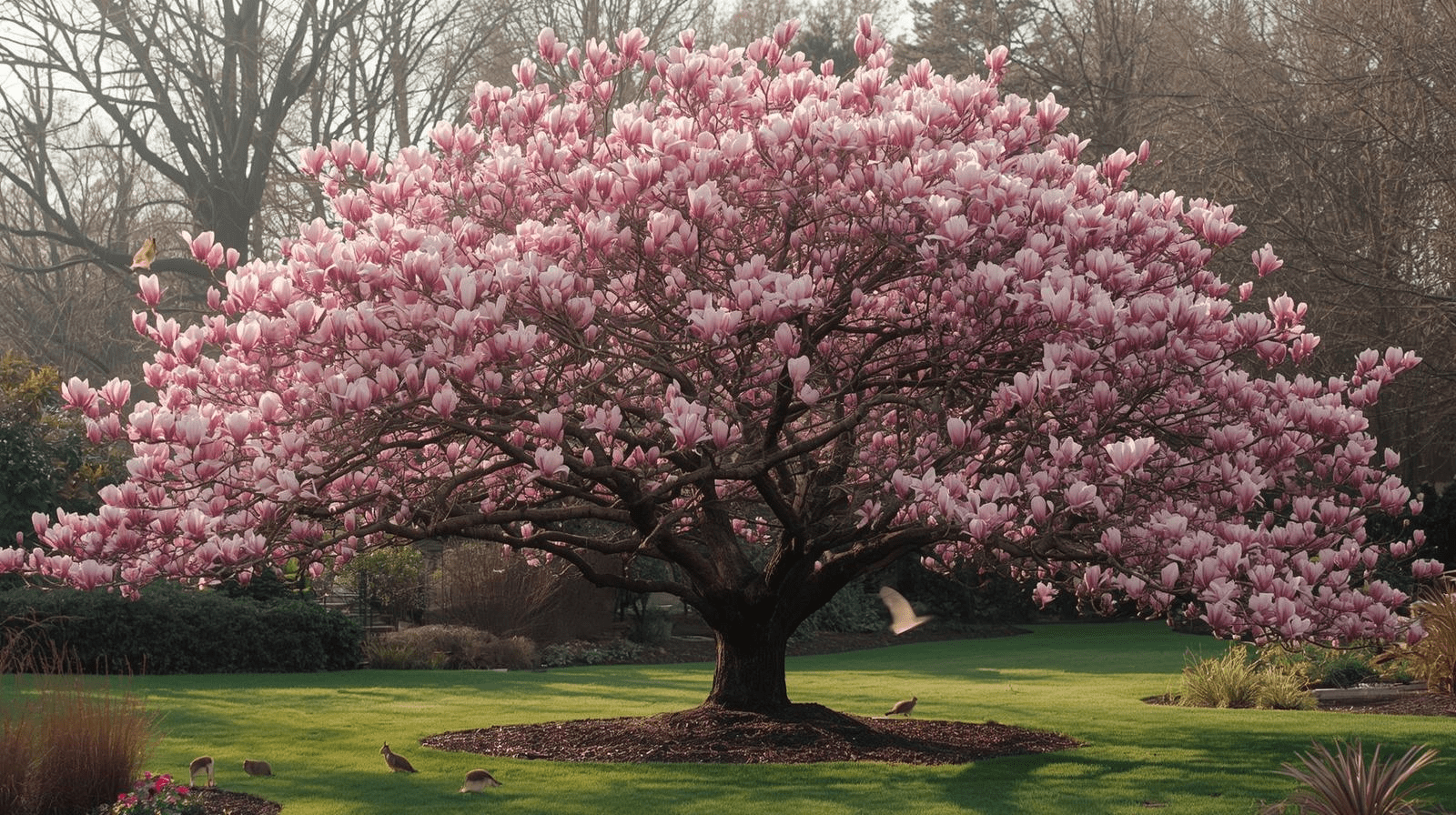

Magnolia × soulangeana: When Pruning Isn’t Improvement

Magnolias are often described as plants that “don’t like pruning”, which is true but not especially helpful. What’s more accurate is that Magnolia × soulangeana doesn’t benefit from it.

In older gardens, Magnolias are frequently cut to balance shape, lift canopies, or reduce spread. The intention is reasonable. The result rarely is.

Wounds take years to close. Growth responses are slow and often poorly placed. More importantly, flowering suffers — not just the following spring, but sometimes for several years after.

I’ve seen Magnolias pruned lightly, correctly, and sparingly, only to lose the very quality that justified keeping them in the first place.

What they need instead is space and patience. If they don’t fit their position anymore, pruning doesn’t solve that problem — it only delays it. In mature gardens, leaving a Magnolia alone is often the most skilled decision you can make.

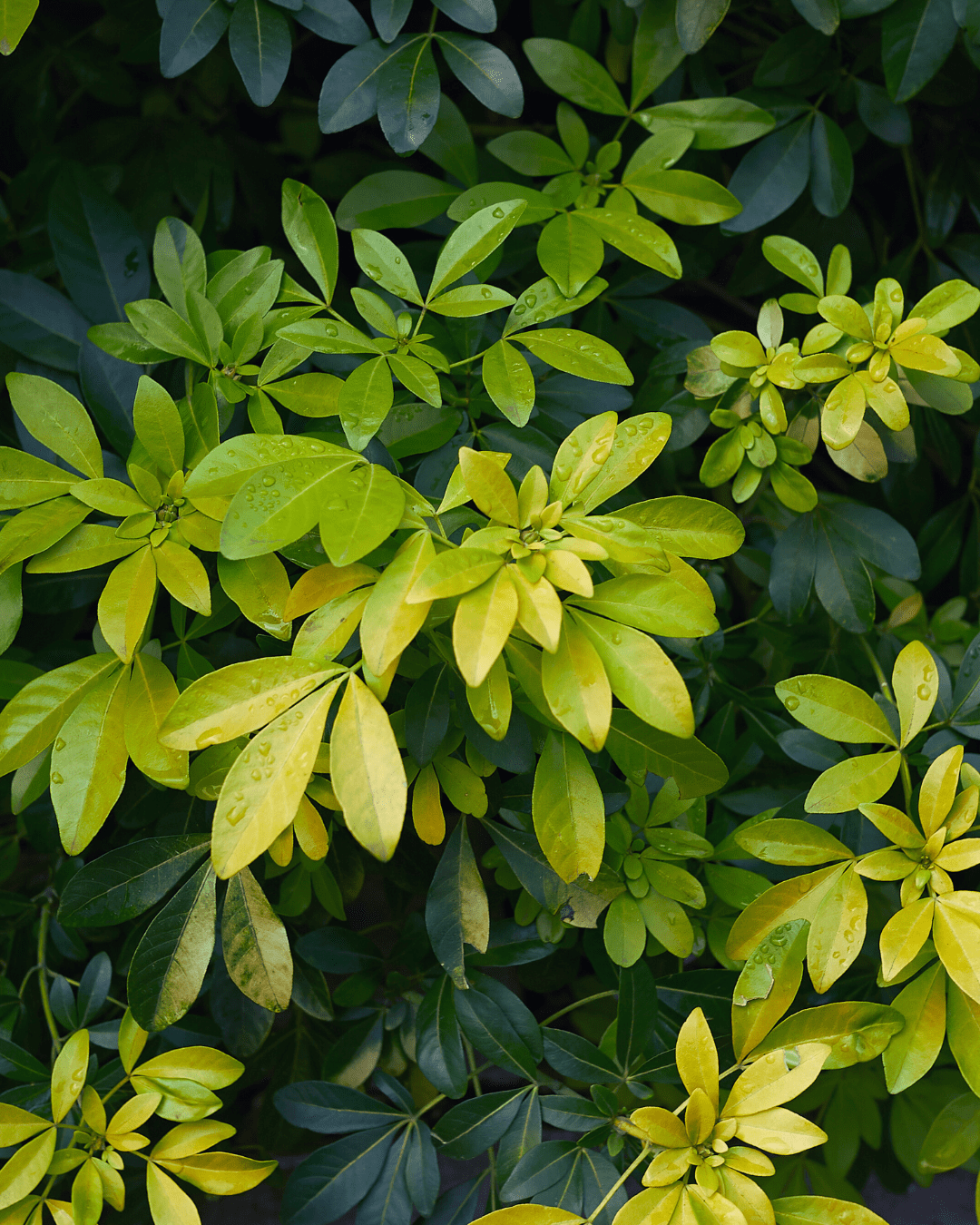

Choisya ternata: When a Shrub Stops Forgiving

Choisya ternata is often described as easy and reliable, and in young gardens that’s true. Early on, it responds well to light pruning after flowering. Growth is steady, foliage is dense, and the plant seems unbothered.

What changes with age is its margin for error.

In older gardens, I began noticing the same pattern repeatedly. Choisya that had been lightly shaped every year started to thin at the base. Regrowth became slower and more uneven. After pruning, plants would sit static for months, sometimes longer, before reluctantly pushing new shoots.

Nothing dramatic happened. They didn’t die. They just never quite returned to what they’d been.

Over time it became clear that the problem wasn’t timing or technique. It was repetition. Each tidy-up was drawing on reserves the plant no longer had in abundance.

These days, with mature Choisya, I intervene very little. An awkward stem removed cleanly, perhaps. Dead wood if necessary. Otherwise, I leave them to their natural outline — or, if structure is already lost, accept that replacement is kinder than continued correction.

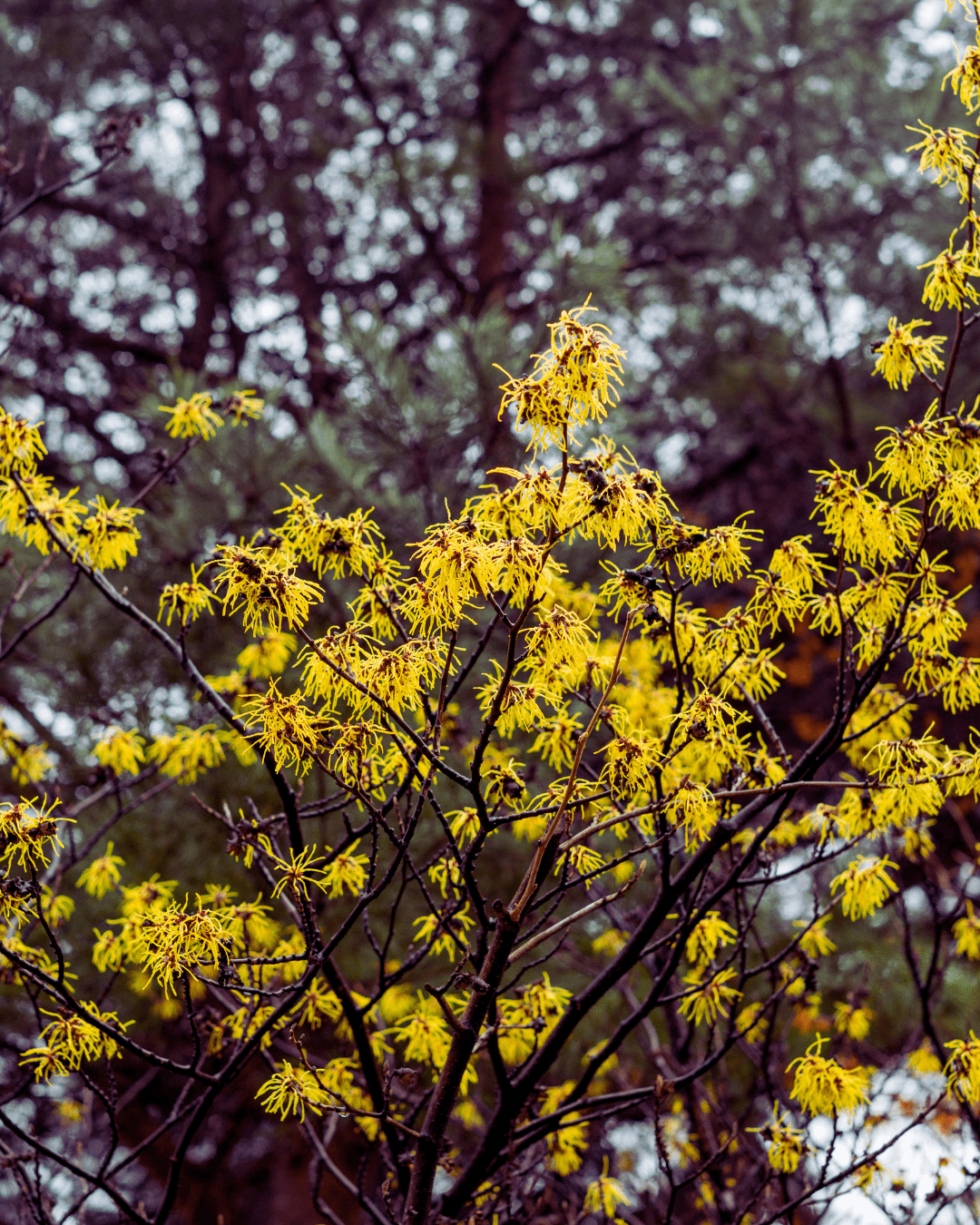

Hamamelis × intermedia: Structure Over Neatness

Hamamelis is one of those shrubs that rewards restraint and punishes interference.

It grows slowly, deliberately, building a framework that takes years to establish. Flowering depends on that framework remaining intact.

In older gardens, I’ve seen Hamamelis pruned to “improve shape” or “open it up”, usually with small, well-meaning cuts. The effect isn’t immediately obvious — which is why the mistake is easy to repeat.

But over time, the consequences show. Flowering wood is lost. Balance is disturbed. Recovery, if it comes at all, is measured in years rather than seasons.

With Hamamelis, neatness is rarely an improvement. Preserving structure matters far more than refining form. Once that’s lost, it’s exceptionally difficult to regain.

The Pattern That Changed How I Prune

Watching these plants over time forced a shift in how I approached pruning in mature gardens.

I stopped asking “When should this be pruned?”

and started asking “What will this plant lose if I do?”

In young gardens, pruning builds energy and structure. In older ones, it often spends it.

That doesn’t mean never pruning — but it does mean recognising that intervention is a risk, not a default. Stability, flowering, and long-term health matter more than short-term neatness.

A Different Way of Looking at Pruning in Mature Gardens

What older gardens teach you — if you’re willing to listen — is that pruning becomes less about action and more about judgement.

Many established shrubs don’t want improving. They want understanding. They want to be left alone long enough to show their natural balance, and intervened with only when there’s a clear, justified reason.

For experienced gardeners and homeowners, this is often the point where things start to feel less straightforward. The rules you’ve followed for years stop delivering the same results. Plants don’t recover as quickly. Familiar routines feel less rewarding.

That’s usually when a second pair of experienced eyes helps most — not to impose change, but to clarify what genuinely needs attention, what should be left alone, and what has quietly reached the end of its useful life.

If your garden is at that stage, we’re always happy to have a conversation. Sometimes all it takes is stepping back, reassessing a few key plants, and allowing the garden to move forward — rather than trying to hold it where it once was.